Introduction In 1895, Vienna became the first city in the world to open a museum devoted exclusively to Jewish history and culture. Fast‑forward to 2025, and the Jewish Museum Vienna (JMW) is celebrating its 130th anniversary with an ambitious exhibition titled “Threads of Memory: 130 Years of Collecting Jewish Vienna.” Scheduled to run April 2 – October 5, 2025, the show promises rare artifacts, digital interactives, and…

Jewish Sites Around Vienna

Remembering Liberation: Vienna’s 80th Anniversary WWII Commemorations in 2025

Introduction On 8 May 2025, Austria marks eight decades since the end of World War II. Vienna’s public squares, synagogues, and museums will host a city‑wide program of remembrance that speaks both to tragedy and to the rebirth of Jewish life. Below is your guide to the key ceremonies, exhibitions, and walking tours that will define this historic anniversary. National Ceremony on Heldenplatz Heldenplatz—pictured above—was where…

Stadttempel Synagogue Bicentennial 2026: 200 Years of Vienna’s Main Synagogue

Introduction When the Stadttempel opened its doors in 1826, it was the only synagogue legally permitted inside Vienna’s city walls. Nearly two centuries later, the elegant Biedermeier sanctuary on Seitenstettengasse remains the beating heart of Jewish religious life in Austria. In 2026, the community will celebrate the synagogue’s bicentennial, turning the entire year into a festival of music, scholarship, and interfaith dialogue. Here’s everything you…

Shoah Wall of Names Vienna: Guided Tours & Reflection 2025

Introduction Unveiled in 2021, Vienna’s Shoah Wall of Names Memorial lists the 64,440 Austrian Jews murdered in the Holocaust. By 2025, the site will host an expanded visitor program—guided tours, reflection circles, and digital storytelling—making it an essential stop for travelers seeking both remembrance and understanding. What’s New for 2025 Tour Schedule & Tickets Time Language Price 10:00 German Free 12:00 English €6 donation 14:00…

Karmeliterviertel Revitalization 2025–26: Vienna’s Jewish Quarter Reborn

Introduction Long before it was hip, Vienna’s Karmeliterviertel served as the beating heart of Jewish life in Leopoldstadt. By 2025–26, a €45 million urban‑renewal plan—supported by EU heritage grants—will transform the neighborhood into a walkable, culture‑rich district that honors its past while embracing the future. Here’s what travelers can expect as cranes give way to café terraces and heritage plaques. The Revitalization Blueprint Completion is slated…

Vienna Jewish Film Festival 2025: Spotlight on Global Jewish Cinema

Introduction From March 11–25, 2025, Vienna will once again roll out the red carpet for the Vienna Jewish Film Festival (VJFF)—Europe’s longest‑running showcase dedicated exclusively to Jewish cinema. Now in its 33rd edition, the festival has become a beloved spring tradition for locals and travelers alike, pairing world‑class filmmaking with the city’s storied Jewish heritage. Whether you are a cinephile, a history buff, or simply…

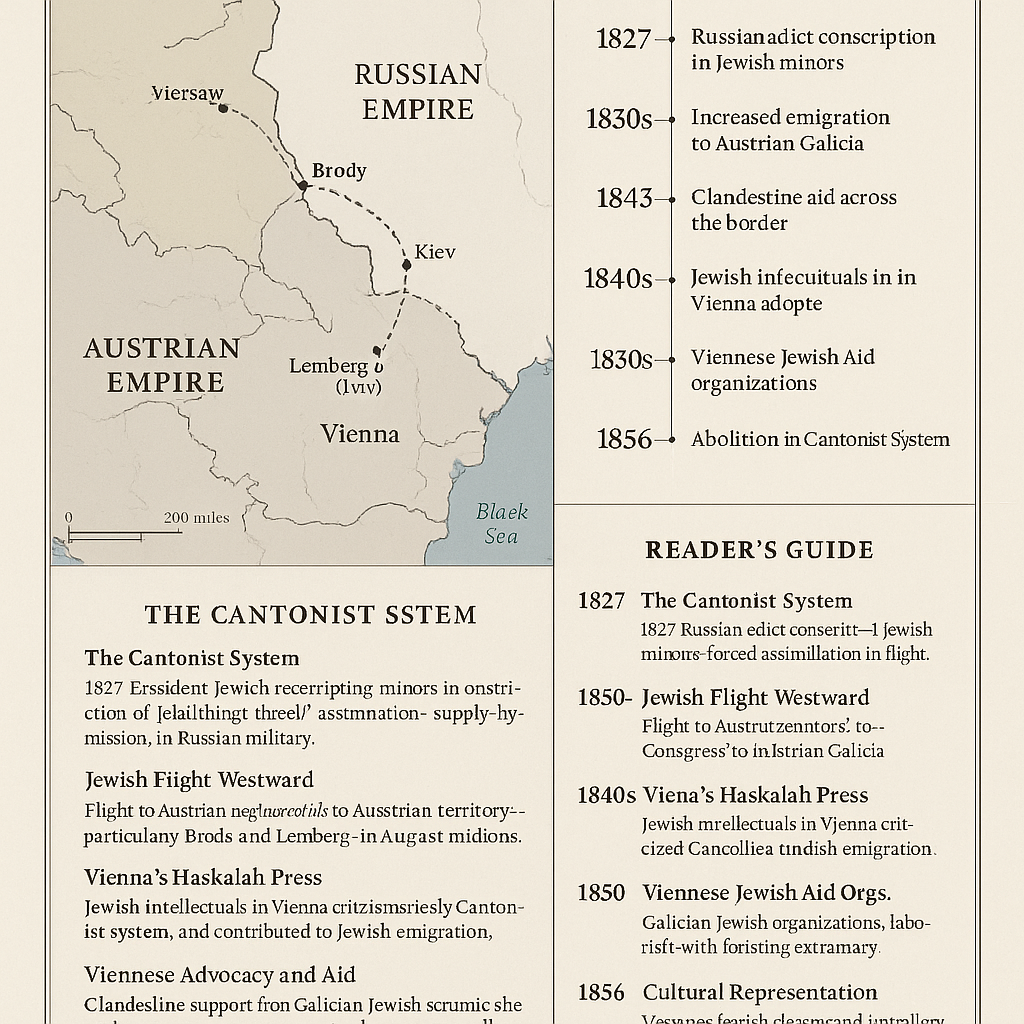

The Cantonist Crisis and Vienna: A Tale of Two Empires and a People in Flight

You are unauthorized to view this page. Username Password Remember Me Forgot Password

The Cantonist Children and Vienna: A Tale of Trauma, Refuge, and Resistance

Introduction From 1827 to 1856, the Russian Empire implemented one of the most brutal policies in Jewish history: the forced conscription of young boys—often as young as six—into military cantonments designed to strip them of their identity, faith, and childhood. Known as the Cantonist system, this edict aimed to convert Jewish children to Orthodox Christianity under the guise of military service. But while these children…

Jewish Life in Vienna: A Hidden Heritage

Vienna, a city known for its rich cultural heritage and historical significance, is also home to a vibrant and historically significant Jewish community. The Jewish community in Vienna has a long and storied history, dating back to the Middle Ages. Despite facing numerous challenges over the centuries, including periods of persecution and displacement, the Jewish community has remained resilient and continues to thrive in Vienna…

Discover Vienna’s Prater – A Guide to Fun, History, and Nature

Introduction Vienna’s Prater is a vibrant destination that combines the excitement of an amusement park with the tranquility of a sprawling green space. Famous for the Wiener Riesenrad, a giant Ferris wheel that offers stunning views of the city, the Prater has been a beloved attraction for locals and tourists alike for over a century. But there’s much more to the Prater than just the…